Filmmaking During The Great Chill: Why We’re Releasing Our Movie on Substack

The story behind “The Coddling of the American Mind” - Part 1

We thought we were prepared for anything, but then the exec declared that it would take just one Twitter user to question why the studio greenlit this project after George Floyd’s death, and their company could be labeled anti BLM.

What? Our project had nothing to do with BLM!

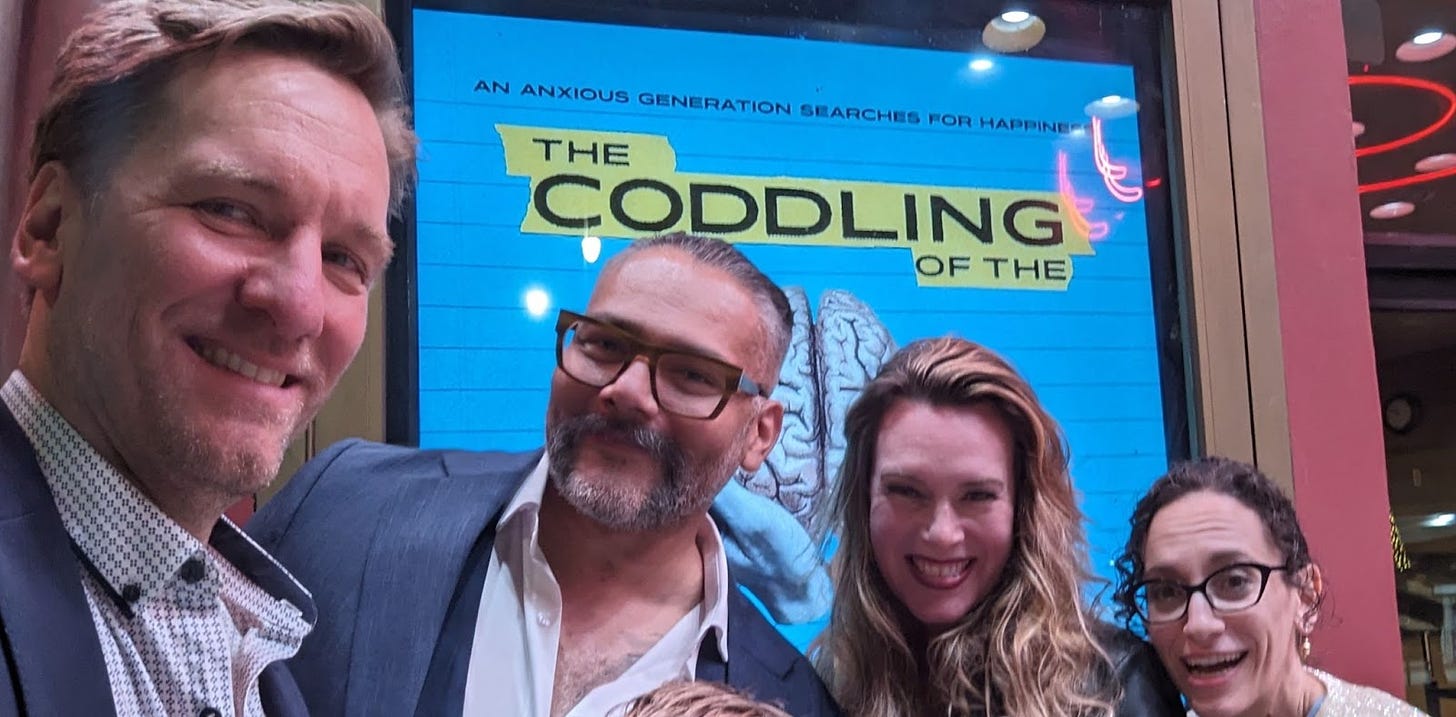

We aimed to help anxious and depressed Gen Zers of every hue find happiness, and we hadn’t even started shooting yet. Our film project bore the title of a New York Times bestselling book, The Coddling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt. But back then—in 2020—that’s about all we had. Well, that and our half-page project synopsis, which we sent to these execs in advance of the meeting.

We didn’t have funding or distribution. We hoped this meeting with one of Hollywood’s top studios would deliver those critical pieces, but it wasn’t looking good.

The execs worried that the project was too heady, and they didn’t like that I was a cis straight white male director. That package of attributes would apparently give critics more “ammo” to target the film for subject matter the execs deemed polarizing.

Polarizing?

Our project offered an antidote to polarized “us vs them” clashes. We referenced that in our half-page synopsis.

The execs had more concerns: They didn’t want to hurt their brand, anger corporate sponsors, or “piss off viewers.”

Piss off viewers!

As we mentioned in our half-page synopsis, our project would show viewers that they’re not fragile. They’re strong. In fact, they’re more than strong. They’re antifragile. How could a message of empowerment piss off viewers?

Turns out the execs didn’t read the half-page overview we sent them. Turns out they had never even heard of the book. (One Googled it during the meeting.)

When a member of our team told them it was a New York Times bestseller, an exec said he didn’t care. Didn’t care?

Why did they even call for the meeting!

The execs did like some aspects of the project, especially the idea of helping young people free themselves from anxiety and depression. They said they would be open to continuing the conversation if we addressed their concerns.

But my wife and I wanted no part of that scene. We could only imagine what those cooks would do in the kitchen. We decided we’d produce the film the way we’re used to, the indie way.

The Great Chill

After producing for the likes of ABC News, Dimension Films, Drew Carey, OWN, PBS, Reason, and Universal Pictures, my wife and producing partner Courtney Moorehead Balaker and I decided to start our own production company. We wanted to maintain Hollywood production values, but ditch the Hollywood groupthink. We were eager to tell the kinds of stories Hollywood won’t tell. So in 2011, we launched Korchula Productions with this mission—making important ideas entertaining.

We produce feature films and other content under the banner of our company and others. We also consult on film and television projects and host filmmaker workshops. When we make documentaries, I direct and Courtney produces, and when we make narratives, we flip it. I produce and Courtney directs.

We have always bristled at the industry’s narrow mindedness. But since 2020, and especially when it comes to hot-button issues like race, sex, religion, and the environment, the industry has gone from narrow minded to borderline fundamentalist.

We watched all the high-profile cancel culture explosions, but we figured the meat of the story would be found elsewhere. Cancel culture is partly about Dave Chappelle, J.K. Rowling, and all the others who have taken their turn behind the crosshairs. But it’s mostly about many other behind-the-scenes people—from up-and-coming comedians, filmmakers, and novelists to the countless agents, publicists, producers, and others who bring art and entertainment to consumers. If expressing certain opinions or exploring certain topics could throw huge stars into crisis mode, how would mere mortals respond?

So as dispiriting as all the highly-publicized eruptions were, we were confronted, again and again, with an obvious but rarely acknowledged fact: When it comes to cancel culture, the chill is worse than the heat.

Controversies involving celebrities attract massive amounts of heat to our screens, but The Great Chill does more damage. The chill spreads cowardice and conformity. The chill suppresses dissidents. The chill prompts us to self censor.

Some ideas emerge as dogma and others as taboo—not on the basis of merit, but on the basis of fear. The result is a monoculture that delivers tedious sameness.

I don’t like the term “cancel culture,” and one reason is because it encourages us to do more of what we humans do naturally—focus on the obvious at the expense of the important. What we see is obvious, but what we don’t see may be more important.

I’d rather talk about “The Great Chill,” but we’re probably stuck with “cancel culture,” at least for now. The term has provoked an array of responses. Some claim it doesn’t exist. Others say it does, but it’s a good thing—because it proportedly elevates black, brown, female and other underrepresented voices. Still others like it because they frame it in “left vs right,” “us vs them” terms, and enjoy seeing the “thems” squirm.

I don’t buy any of that. Not only does cancel culture exist, but it’s a threat to nearly all of us regardless of race, sex or any identity characteristic. It also threatens nearly all of us regardless of politics. In short, the “thems” are nearly all of us.

There exists only one group that enjoys a good deal of protection.

The Eight Percenters

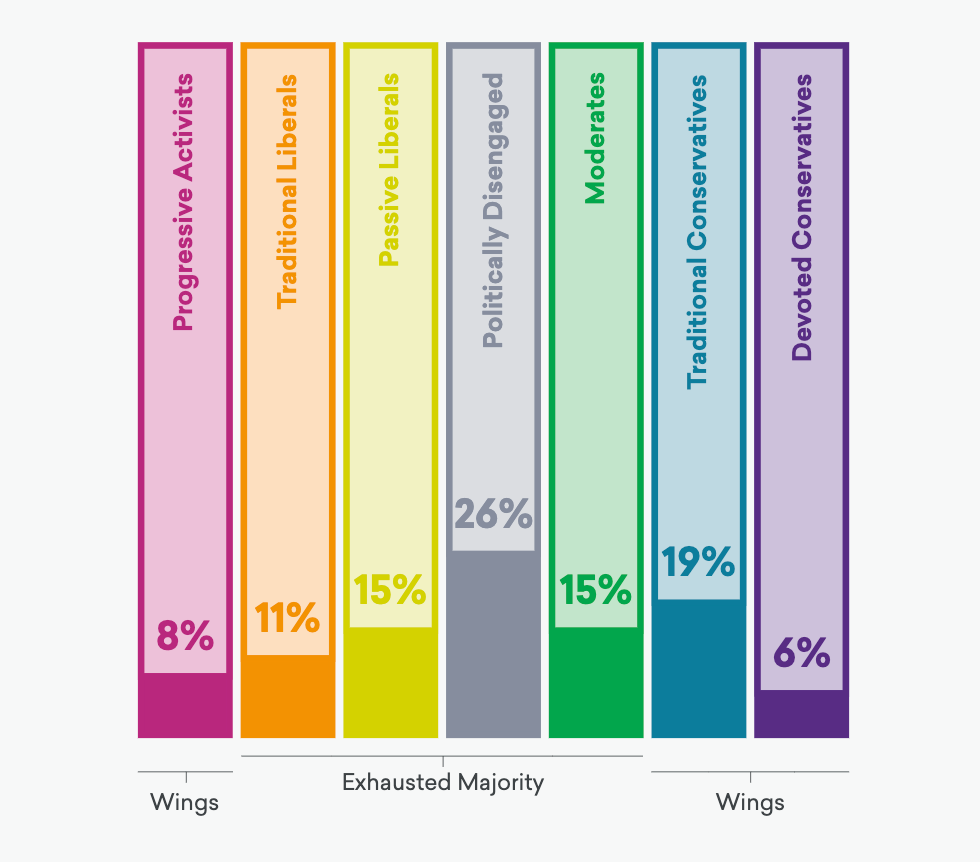

I started to understand the landscape after reading a report called “Hidden Tribes,” which was produced by the British organization More in Common. Instead of hewing to the false binary of left vs right, it reveals America’s seven hidden tribes.

Some tribes lean left and others lean right, but most Americans cluster around the middle of the spectrum. And on issues ranging from racial preferences to speech, a pattern emerged. One of these tribes is not like the other.

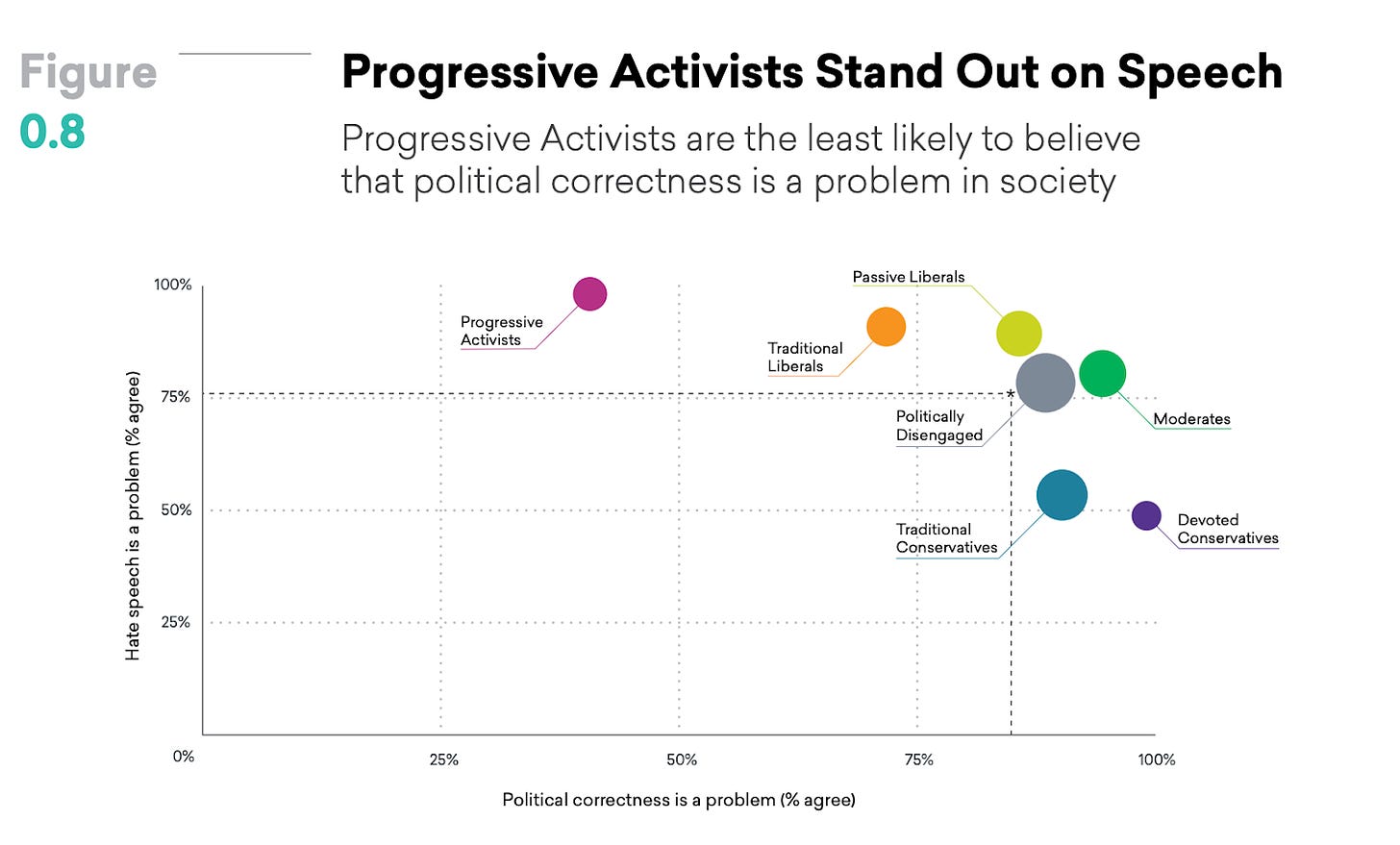

Is political correctness a problem?

Tribes left, right, and center said yes. Only one tribe said no. More in Common calls that tribe “Progressive Activists.” It’s a group that represents only 8 percent of America.

Like the rightmost tribe (Devoted Conservatives), the Progressive Activists are overwhelmingly white and represent a relatively small slice of the American pie. But compared to their conservative counterparts, Progressive Activists enjoy a great deal of cultural influence.

They’re overrepresented in culture-producing industries like academia, media, and entertainment. And that makes the Eight Percenters seem more numerous than they really are. Social media magnifies their impact even more. Progressive Activists are especially likely to be active online and to post about politics. Although all tribes indulge in some mobbing, cancel culture has been mostly driven by Progressive Activists.

Tribe members like to pretend that minority groups share their progressive worldview, but polling data often tell a different story. And one need only look at how Progressive Activists treat minorities who step out of line, to see that the Eight Percenters’ top concern isn’t elevating underrepresented voices. It’s elevating their tribe’s peculiar brand of progressive politics.

Here are some examples from our circle of friends and associates:

Karith Foster, a black DEI dissident we profiled in our film Can We Take a Joke?, found herself disinvited from a speaking engagement at a major college because she does not conform to the divisive “us vs. them” style of diversity workshops favored by so many university administrators.

Surbhi came to America from India for college. She said something taboo and promptly got cancelled. Today the Gen Z standup comic steers clear of certain topics and sees her comedian peers do the same.

A Latino comedic actor friend quickly found himself jobless. The new media company that had recruited him so eagerly, abruptly fired him after his style of comedy suddenly became problematic in post-2020 America.

Eli Steele, a black documentarian, ran into problems distributing his film on Amazon, problems that seemed to stem from his taboo take on the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

When a producer friend of mine from a major media outlet hoped to add some intellectual diversity to an upcoming program about race in America, he asked me to suggest some heterodox black thinkers. I provided a list that included an entrepreneur/podcaster (Kmele Foster) and two university professors (John McWhorter and Walter Williams). My friend's white boss rejected these potential interview subjects as “too extreme.”

RELATED:

America Wants Problematic Comedy: Ricky Gervais and Dave Chappelle Keep on Winning

Minorities Don’t Like Racial Preferences: 5 Ways the Media Hides the Truth

Sorry NBC and The View, Most Minorities Oppose Racial Preferences

From The New York Times to Colin Kaepernick’s Netflix Series: The Mainstreaming of Microaggressions

In some cases, the monoculture quickly amends its unwritten rulebook to cater to new identity-based concerns. It issues new directives that undermine not just artistic freedom, but also the value of diversity that Eight Percenters supposedly regard as sacred. If they don’t abide by the always-evolving rulebook, the Eight Percenters will torpedo “diverse” projects, deny roles to minority actors, and target artists from underrepresented groups.

Take first-time female directors like Meg Smaker.

Smaker directed a powerful documentary called Jihad Rehab, which was good enough and progressive enough to be embraced by Sundance programmers and reviewers from outlets like The Guardian and Variety. But none of that mattered when an identity-driven Sundance mutiny sunk her film (now renamed The Unredacted). Overnight Smaker went from Sundance darling to Sundance heretic.

The one-name gay Latino director Terracino experienced a similarly swift reversal of fortune. The veteran of top-tier LGBTQ film festivals had every reason to expect his latest project, Waking Up Dead, to be embraced by the film community. But the reaction from festival organizers surprised him:

“My gay lead character [is initially] transphobic, which is something I wanted to explore — transphobia within the gay community — and they had an issue with that. They were scared to show a film with a transphobic lead.” He says he was also asked: “‘Why does your Latino lead have to bond with a white woman?’ I was really taken aback by that one. Here I am, a gay Latino filmmaker, and I have to answer about bullshit racial politics?”

Outfest passed on Waking Up Dead, then Frameline and NewFest followed suit, meaning the three biggest LGBTQ festivals passed on the latest offering from a once-celebrated director.

Frozen Projects

Meanwhile Courtney and I continued to feel the freeze in our own projects.

Our 2018 narrative feature Little Pink House stars two-time Academy Award nominee Catherine Keener and Emmy nominee Jeanne Tripplehorn. It dramatizes the true story of a working-class woman named Susette Kelo who fights back against powerful politicians who are bent on bulldozing her neighborhood for the benefit of Pfizer Corporation, which had high hopes for a new drug called Viagra. The legal battle continued all the way to the US Supreme Court, and culminated in 2005’s infamous Kelo decision.

Thanks to Little Pink House, Courtney was now in the mix to direct other female-driven real-life features. A producing team wanted Courtney to direct their feature, and Courtney read the script with great excitement. But she soon discovered that the “based on a true story” script blatantly disregarded historical fact in service of identity-based fiction.

Courtney offered to rewrite the script for free—the actual true story is extremely compelling, but it’s nuanced. And these days, nuance can be problematic. But the producers remained committed to their reimagining of history, and ultimately Courtney chose her principles over what could have been a lucrative and exciting opportunity.

The chill quickly froze another project, one of our own.

Since we were now in the “true life” space, we began developing another narrative biopic. Like Susette Kelo, Thomas Sowell is an under-appreciated American hero whose life story reads like a screenplay. How did a black orphan born in the Jim Crow South rise to become a maverick genius courted by presidents?

Sowell is a hero of mine and I’ve been reading his books for a long time. When I was in college I wrote to him—the old-school way, with a stamp and everything. To my delight, he wrote back. When my son turned seven, we started reading Sowell books together.

Courtney and I wanted to move swiftly because Sowell turns 94 in June, but after posing queries to various gatekeepers, we were told that there’s no way two white filmmakers would be allowed to make a movie about a black man. Never mind that the black man in question disagreed. In fact, Sowell already agreed to have a white documentarian tell his story. Our culture definitely needs more Sowell, but we also had to acknowledge what we were up against. Although we hope to revisit the project in the future, we decided to shelve the Untitled Sowell Project.

RELATED:

Why You’ll Be Watching Fewer Problematic Movies: The hidden side of cancel culture at Sundance

Dissidents Need Not Apply: Is Campus Groupthink Coming to Hollywood?

If You Know You’re Right, Step on the Gas! The Rise of Fundamentalism in Academia and Hollywood

Around the same time, we were gearing up to produce a feature documentary about the COVID response, one that would focus on an unlikely dissident—Sweden. How could the global community’s golden child turn so naughty so fast?

Although we were prepared to be surprised, the Nordic nation’s relatively hands-off approach struck us as wise. We were also blessed with excellent resources as we had Sweden-based friends who were immersed in the issue. The natural experiment had the makings of a great story—high stakes plus a giant, unresolved question that would be answered in a couple of years: Which nation would weather the COVID crisis best?

We called our project Mad World, and we were ready to document the global contest. But it soon became apparent that the monoculture had already decided which strategies were winners and losers. What was particularly concerning was how distributors seemed to be choosing conformity over debate.

We made a judgment call. We weren’t going to tell investors the project could reach large audiences if distributors wouldn’t release such a film. Mad World was dead.

The Eight Percenters vs. “The Coddling”

The Great Chill might have frozen some other projects, but we wouldn’t let it claim The Coddling of the American Mind. It would be one thing if the studio execs who worried that our project would “piss off viewers” had a point. If we had no shot at reaching an audience, we should choose a different project.

But we knew our project had an audience. It was based on a book that spent nine weeks on The New York Times bestseller list. Greg and Jon’s work was named one of the best books of 2018 by The New York Times, The London Evening Standard, and The New Statesman. It attracted a massive amount of earned media, including from Real Time with Bill Maher and CBS This Morning.

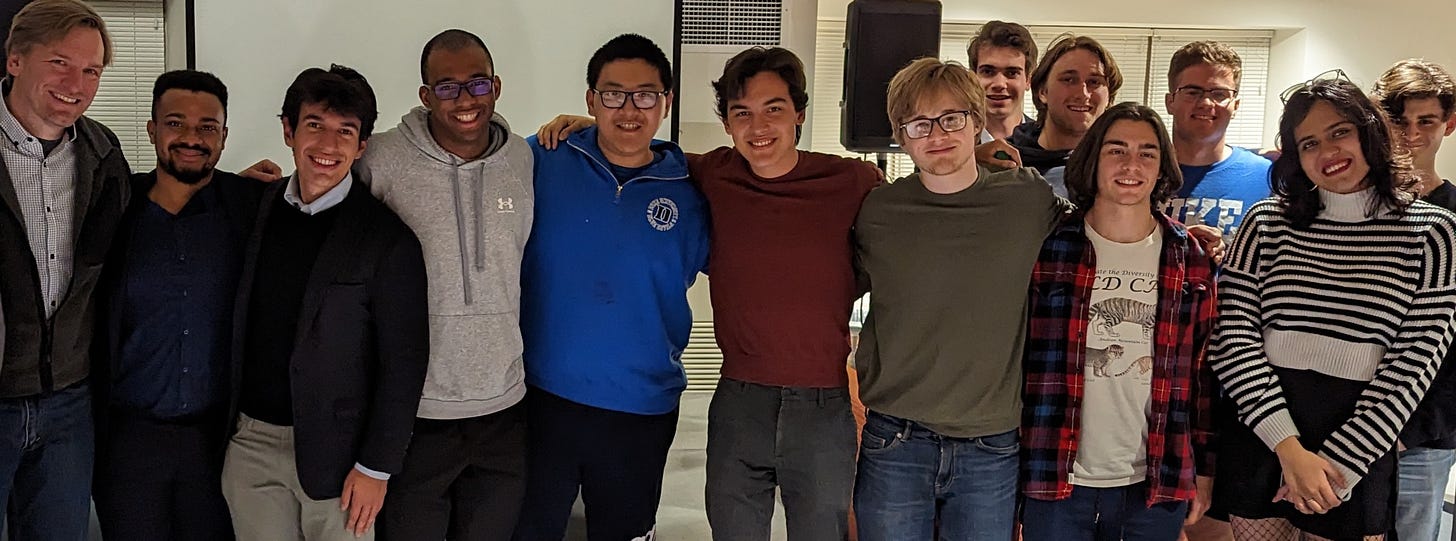

And when we crafted the film, we knew we didn’t want to just preach to the converted. We wanted to reach viewers from many tribes, so we tapped our politically diverse network for feedback. We knew these people would tell us what we needed to hear, not what we wanted to hear. We incorporated their notes and held sneak peek screenings across the nation.

Again and again, we accumulated more evidence that we might be onto something.

Audiences that were diverse based on age, race, sex, and politics continued to embrace the film. Each screening generated requests for more screenings, and each Q&A period went much longer than scheduled.

At a screening for about 40 undergrads, viewers filled out anonymous questionnaires. We asked them to use their own words to describe the film. The most common responses clustered around synonyms for “stimulating” and “truthful.”

Here is some of what anonymous Gen Zers told us:

“As someone on the inside (GenZ), after seeing the destruction of lives around me — including very close friends — this film gives me hope and further inspires me to share this message.”

“I am not a victim. I am stronger than what I was told.”

“I won’t coddle my kids.”

“It helped me find words for a lot of my feelings”

“May times I caught myself thinking, ‘Oh, I’ve done that,’ or ‘I’ve had thoughts like that.’”

“Don’t let toxic ideas rule your life.”

“We need to tell kids more stuff like this.”

We knew those studio execs were wrong.

Sure our film might piss off some viewers, but it would connect with many others.

We knew there was an audience for our film. What we didn’t know was how to reach that audience.

But we were determined to find out.

Part 2: Attack of the Eight Percenters: Why We’re Releasing Our Film on Substack

Ted Balaker is a filmmaker, and former network newser and think tanker. His recent work includes Little Pink House starring Catherine Keener and Jeanne Tripplehorn, Can We Take a Joke? featuring Gilbert Gottfried and Penn Jillette, and the new feature documentary based on the bestselling book, The Coddling of the American Mind, by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt. Stream it here.

Thanks for sharing these thoughtful insights into your filmmaking experience Ted! What a shame that "Mad World" did not make it. My husband and I watched "The Coddling" and will encourage our readers to watch it as well (especially with their teens). You provided a piece of sane ground between the extremes. Thanks for your excellent work! Looking forward to part 2.

"The Coddling" was excellent, and I will definitely be checking out your other films! Thank you for weathering the chill and standing for the truth. And please make the Thomas Sowell movie!!!